INVASIVE MUSSELS

Learn more about zebra and quagga mussels

Zebra Mussel — Fish & Wildlife (left). Quagga Mussel — National Park Service (middle). Native Rocky Mountain Ridge Mussel (right).

What Invasive Mussels?

Zebra and quagga mussels are closely-related mollusks that originate from freshwater lakes in Russia and Ukraine and are non-native to North America. They live in freshwater – such as lakes and rivers – and are invasive. They are known to encrust and corrode hard surfaces and cause serious harm to waters where they become established.

Fortunately, as best we know, the Okanagan is still free from invasive mussels. It’s up to us to help keep it that way.

Note: The Okanagan does have native mussels that are protected species. One being the Rocky Mountain Ridged Mussel, a much larger mussel that can grow to 12.5 cm (almost 5 inches) long, and Floater Mussels which are between 12.5 and 18 centimeters. Learn more about these mussels here (page 2).

Where did zebra and quagga mussels come from??

They were first introduced to Canada’s Great Lakes region and the United States in the 1980s after ballast water was discharged by vessels travelling from Europe.

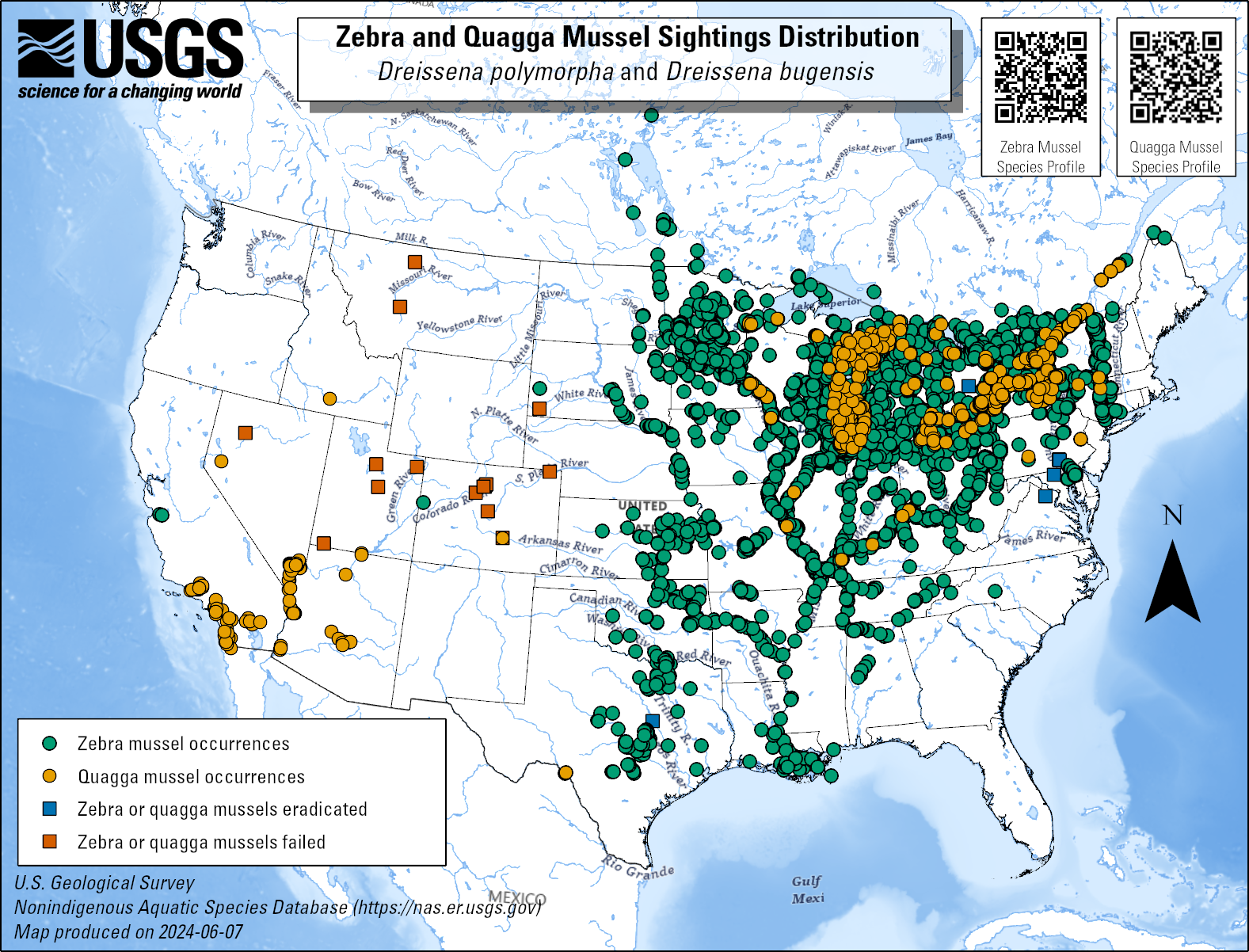

Where are they now?

Invasive mussels have been in the Great Lakes in Ontario and Quebec since the late 80’s and have been spreading ever since through U.S. states, including California, Nevada, Arizona. In 2013 – the same year we launched our “Don’t Move A Mussel” campaign – invasive mussels were discovered in Lake Winnipeg, Manitoba. They have since spread to Cedar Lake, Man. And this last fall, it was announced that zebra mussels were discovered in Clear Lake, Man., as well as in New Brunswick, and quagga mussels were found in Idaho’s Snake River.

The discovery of mussels in the Snake River is of great concern since it is a tributary to the Columbia River which connects to the Okanagan River, and is only an 11-hour drive to the B.C. border.

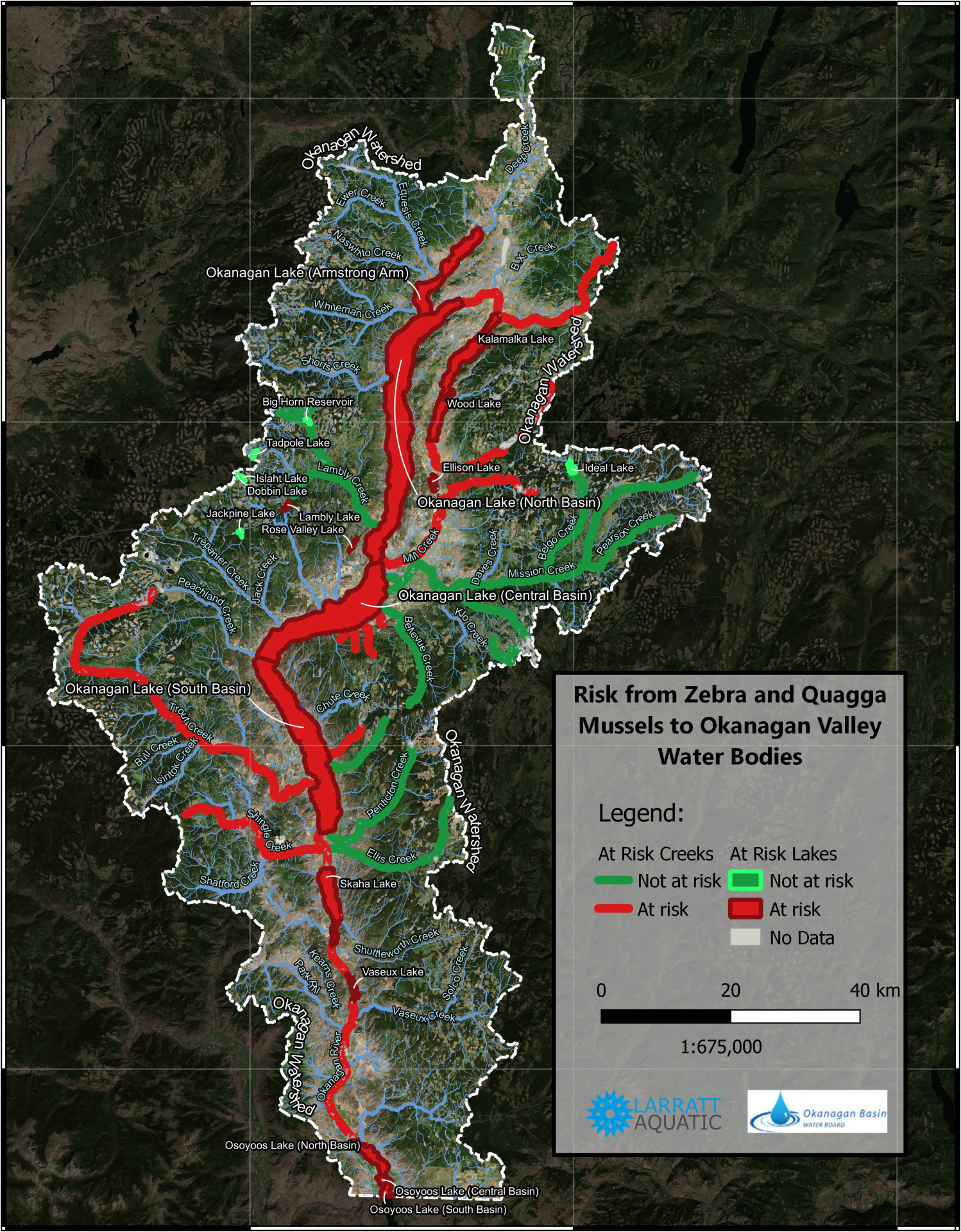

In addition, recent water sampling in the Okanagan indicates that local waterways are at high risk for invasive mussels. This is due to warm water temperatures and water chemistry, including high calcium that gives local waters like Kalamalka Lake its beautiful blue-green colour. An additional risk is the Okanagan’s attraction for water recreation.

In response, we at the Okanagan Basin Water Board have called for a temporary moratorium on out-of-province watercraft entering B.C. until 1) we know if Idaho was successful in its efforts to eradicate the mussels and 2) the Province of B.C. has been able to address the gaps in its Invasive Mussel Defence Program.

With the mussels now closer than ever to B.C., preventing their spread is more critical than ever.

Prevent Aquatically Transmitted Species

It wouldn’t take long for the mussels to get established once they arrive. Each female can produce about 1 million eggs per year. And in some areas with warm waters, like Lake Mead, there have been six to eight reproductive cycles a year.

The mussels can be spread unknowingly by boaters, fishers and other well-meaning nature lovers as well as through aquarium plants. At their youngest stage, the invasive mussels are the size of a grain of sand. At their largest they are the size of your thumbnail (1.5 to 2 cm). They are often brought in on boats and other recreational water toys (e.g. kayaks). But they can also come in on hip waders, fishing tackle boxes, life jackets and other objects that have spent time in infested waters.

Be sure to clean, drain and dry all your recreational water toys and supplies and properly dispose of any aquarium plants and animals — never flush them since they can spread disease!

Where does the “zebra” mussel get its name?

Both invasive mussel species are sometimes referred to as “zebra” mussels because they both have light and dark alternating stripes. Quagga mussels are actually a distinct, but similar, species named after the quagga – an extinct mammal which closely resembled and was related to the zebra.

What are the implications?

A study conducted for the Okanagan Basin Water Board found that an invasion of zebra and/or quagga mussels in the valley could impact

- Our drinking water intakes and distribution system

- Stormwater and treated sewage system outfalls

- The safety of our drinking water with the promotion of toxic algae

- Aquatic infrastructure (e.g. marinas, public and private docks, Kelowna’s WR Bennett Bridge)

- Motorized and non-motorized watercraft and water recreation equipment (including boats, sea-doos, kayaks, paddle-boards, fishing gear, float planes, etc.)

- The natural ecology of the lake, putting at risk native species and resulting in the collapse of our fishery

- Real estate values, especially waterfront property

- Enjoyment of our beaches with the introduction of razor-sharp shells, and the smell of decaying mussels

- Okanagan tourist economy – with fewer visitors due to our fouled beaches and loss of our fishery

- Our economy with the loss of tourism jobs and increased taxes to help manage the mussel infestation and its impact on local government infrastructure

What are the cost implications?

A study conducted for the Okanagan Basin Water Board in 2013 found the cost to our region could be at least S42 million each year in lost revenue, added maintenance of aquatic infrastructure and irreparable ecological damage. In 2015. the Pacific Northwest Economic Region (PNWER) estimated the cost of an invasion at S500 mill. annually to the Pacific Northwest. And in 2023, the Government of B.C. issued a report suggesting an infestation would cost the province $64 to $129 mill. annually, but this does not include the damage to healthy aquatic ecosystems, including the impact to fish.

Spread the message, not the mussel.

Learn ways to help spread the message and download the kit.